Why an American went to Cuba for cancer care.

Cuba has faced more than 50 years of US sanctions. Now, for the first time, a unique drug developed on the communist island is being tested in New York state. But some American cancer patients are already taking it – by defying the embargo and flying to Havana for treatment.

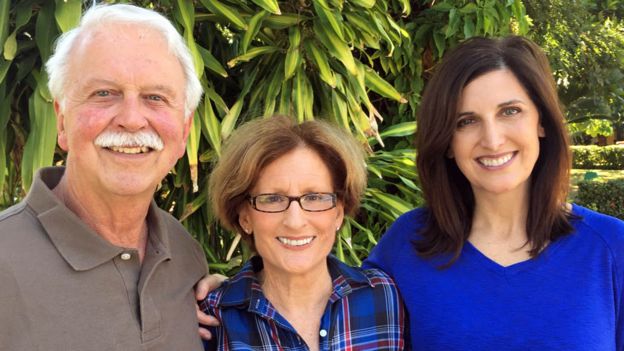

Judy Ingels and her family are in Cuba for just six days. They have time to go sightseeing and try out the local cuisine. Judy, a keen photographer, enjoys capturing the colonial architecture of Old Havana.

And while she is in the country, Ingels, 74, will have her first injections of Cimavax, a drug shown in Cuban trials to extend the lives of lung cancer patients by months, and sometimes years.

By travelling to Havana from her home in California, she is breaking the law.

The US embargo against Cuba has been in place for more than five decades, and though relations thawed under President Obama, seeking medical treatment in Cuba is still not allowed for US citizens.

“I’m not worried,” Ingels says. “For the first time, I have real hope.”

She has stage four lung cancer and was diagnosed in December 2015. “My oncologist in the United States says I’m his best patient, but I have this deadly disease.”

He does not know she is in Cuba. When she asked him about Cimavax, he had not heard of it.

“But we’ve done a lot of research – I’ve read good things,” Ingels says. Since January, Cimavax has been tested on patients in Buffalo, New York state, but it isn’t yet available in the US.

Ingels, her husband Bill and daughter Cindy are staying at the La Pradera International Health Centre, west of Havana. It treats mostly foreign, paying patients like Ingels, and with its pool complex, palm trees and open walkways, La Pradera feels more like a tropical hotel than a hospital.

This trip from their home in California, together with a supply of Cimavax to take back to the US, will cost the Ingels family more than $15,000 (£12,000).

Cimavax fights cancer by stimulating an immune response against a protein in the blood that triggers the growth of lung cancer. After an induction period, patients receive a monthly dose by injection.

It’s a product of Cuba’s biotechnology industry, nurtured by former President Fidel Castro since the early 1980s.

Ironically, Cuba’s biotech innovations can partly be explained by the US embargo – something Castro continually railed against. It meant Cuba had to produce the drugs it could not access or afford. And medications like Cimavax – low-tech products that could be administered in a rural setting – were developed to fit the Cuban context.

Now the industry employs around 22,000 scientists, technicians and engineers, and sells drugs in many parts of the world – but not in the US.

And although the Cubans will not reveal the cost of producing Cimavax, it is cheaper than other treatments.

For Cuba’s residents, all health care is free. One beneficiary is Lucrecia de Jesus Rubillo, 65, who lives on the fifth floor of a block of flats in the east of Havana

Last September she was given two or three months to live. What began as pain in Lucrecia’s leg, was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer that had spread.

She had chemotherapy. “That was really very hard,” she says. “It gave me nausea, and it hurt. But my kids asked me to fight, so I did.”

After radiotherapy, Lucrecia began Cimavax injections. Now she is strong enough to walk up the five flights of stairs to her home, and her persistent cough has diminished. She feels better, more hopeful, and is thinking about what to do next.

“Perhaps I’ll go to Spain to visit my kid,” she says. “I feel happy, and I’m still dreaming of the future, but I also feel sadness. I’ve had a lot of friends who’ve died of cancer, and they never had the chance I’m having with these injections. I feel privileged.”

Her doctor is Elia Neninger, an oncologist at the Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital in Havana. Neninger is one of the principal clinicians to trial Cimavax on patients since the 1990s.

“Lucrecia arrived incapacitated by her disease in a wheelchair,” Neninger remembers. “Now the tumour on her lung has disappeared, and the lesions on her liver aren’t there either. With Cimavax, she’s in a maintenance phase.”

In Cuba, specialists like Neninger do not talk about curing cancer – they talk about controlling it and transforming it into a chronic disease. She has treated hundreds of patients with Cimavax.

“I never thought I’d work on something that would improve the lives of so many people,” she says. “I have stage-four lung cancer patients who are still alive 10 years after their diagnosis.”

But mostly Cimavax is proven to extend life for months, not years. And it does not help everyone. In trials, around 20% of patients haven’t responded, Neninger says, often because the disease is very advanced, or they have associated illnesses that make treatment more difficult.

Nonetheless, Dr Kelvin Lee is impressed. He is the Chair of Immunology at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, where the American trials of Cimavax are taking place.

It is the first time a Cuban medication has been trialled in the US and required special permission because the embargo prohibits most collaboration and trade.

Cancer immunotherapy is getting more expensive in the US, Lee says. A cheap vaccine that can be administered at primary care level is very attractive. And he thinks it is possible that Cimavax could be used to prevent lung cancer, too.

“If we could vaccinate the high-risk smokers to prevent them from developing lung cancer, that would have an enormous public health impact both in the United States and worldwide.”

This has not been proven, however, and the initial US trials of Cimavax only began in January.

There is political uncertainty, too. On the campaign trail before his election, President Trump said he would reverse the thaw with Cuba that began under the Obama administration unless there was change on the island, which is governed as a one-party state.

“Our demands will include religious and political freedom for the Cuban people, and the freeing of political prisoners,” Trump said on the campaign trail in Miami.

So far, Cuba has not made it to the top of his in-tray. There is a large constituency of Americans who believe that Cuba does not deserve the kind of recognition and status the association with the Roswell Park Cancer Institute brings.

But Lee thinks political arguments against US-Cuba collaboration are misplaced.

“The gas we put in our cars, the iPhones we tweet from, the shoes we buy our kids – all come from countries that the United States has fundamental differences with regarding women’s rights, freedom of speech, personal liberties. Yet that has never stopped us from working with them in areas that benefit the people in both countries.”

For now, Bill Ingels, Judy’s husband, isn’t worried about falling foul of US authorities.

“I told them I was coming for educational purposes,” he says. “And I am learning about cancer and medication! I’m basically a very honest person, but if I have to, I will lie.”

Ingels will not know if the vaccine has made a difference until she has a scan in three months.

“We feel pretty positive, and we thought this would be a great experience and journey for my family to take together. It’s the first time I’ve felt up since I was diagnosed.”

Cindy Ingels, Judy’s daughter, is a nurse – she will administer the Cimavax shots to her mother back home in California.

“Even if she remains stable – that it maintains the tumour size, and it doesn’t worsen – we’d be happy with that,” she says. “If a tumour decreases from what it is now, that would really be a miracle.”