‘It’s going to happen’: is the world ready for war in space?

When you hear the phrase “space war”, it is easy to conjure images that could have come from a Star Wars movie: dogfights in space, motherships blasting into warp speed, planet-killing lasers and astronauts with ray guns. And just as easy to then dismiss the whole thing as nonsense. It’s why last month’s call by President Trump for an American “space force”, which he helpfully explained was similar to the air force but for err… space, was met with a tired eye-roll from most. But there is truth behind his words. While the Star Wars-esque scenario for what a space war would look like is indeed far-fetched there is one thing all the experts agree on.

“It is absolutely inevitable that we will see conflict move into space,” says Michael Schmitt, professor of public international law and a space war expert at University of Exeter in the United Kingdom.

Space has been eyed up as a military asset almost since the beginning of the space race. During the cold war, Russia and America imagined many kinds of space weapon. One in particular was called the Rods from God or the kinetic bombardment weapon. It was a kind of unmanned space bomber that carried tungsten rods to drop on unsuspecting enemies. As they fell from orbit, the rods gathered so much speed that they delivered the explosive power of a nuclear bomb, but without the radioactive fallout. However, such systems are hideously expensive, probably outlawed by international treaties and the satellites that carry them are easy targets to shoot down.

What has prompted this latest interest in space war is that the means by which one country can attack another in space have changed dramatically. These days, a frontline space war soldier is most likely to be a state-sponsored hacker sitting at a computer terminal sending rogue commands to confuse or shut down an enemy’s satellites.

“I am convinced beyond a scintilla of doubt… It’s going to happen,” says Schmitt.

Space war is inevitable because today’s modern militaries use space for everything, from spy satellites to a soldier on a mountaintop using satnav to figure out exactly where he or she is. “The reliance upon space is truly extraordinary in contemporary conflict,” says Schmitt. And in any war, one side will seek to deprive the other of their ability to function. In this day and age, that means attacking the satellites.

In May 2014, the Russians launched a mysterious satellite that was seen to be manoeuvring in orbit. Some thought it was the Russians testing a future space weapon because such orbital gymnastics are exactly what would be expected from an attack satellite designed to approach another and put it out of operation. Indeed, the Russians have a history of testing such spacecraft.

“The original but larger Russian manoeuvrable military satellite, Polyot, dates to 1963,” says Brian Harvey, a space analyst and author of The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (Springer). And it is not just the Russians. “The real experts in developing small, manoeuvrable satellites that change orbits and make multiple interceptions are the Chinese in their Shijian series,” he says.

The Chinese have demonstrated other military space options, too. In 2007, they destroyed one of their own weather satellites using a missile launched from Earth. The FY-1C satellite was at an altitude of 865km and was hit by the missile travelling at 8km/s. The satellite disintegrated into an estimated 150,000 pieces of space debris.

Yet Schmitt thinks that any conflict in space is unlikely to start with such brutal measures. “The immediate form would be cyber-attacks, either against the satellites or the ground stations that control them. It depends on the nature of the conflict whether you go beyond that,” he says.

Although treaties already exist that say you can’t put military installations on the moon or weapons of mass destruction into orbit, there is a decidedly grey area.

“Many things can be used for peaceful and military purposes,” says Jan Wörner, director general of the European Space Agency (ESA).

Take the Russian and Chinese manoeuvring satellites as an example. Although Harvey says that these particular tests are probably for military purposes, the ability to rendezvous in space is also an essential technique for China to master in order to achieve its ambition of bringing back moon rock samples to Earth.

Wörner grapples with such duality on a daily basis. The ESA is mandated to pursue only peaceful space exploration and utilisation. As part of that, it is developing ways of removing old spacecraft and pieces of space debris from orbit. However, critics have pointed out that if a piece of technology can track down and grapple a dead satellite out of orbit, it can do the same with a live one – thus becoming a potential weapon.

It is through the creation of space debris that any conflict in orbit would have decidedly Earthbound consequences for us all.

“Space is different from 50 years ago. Then, it was a race between superpowers; today, it is everything. We all rely on space each and every day,” says Wörner. When we wake up in the morning and look at the weather forecast, when we use a satnav to get somewhere we’ve never been before, when we listen to the radio or make a mobile phone call, when we buy things online, the chances are that these signals are mediated by satellites in some way.

The debris cloud created by blowing up satellites can easily collide with other satellites, destroying them and triggering a chain reaction that could swiftly surround the Earth with belts of debris. Orbits would become so unnavigable that our access to space would be completely blocked, and the satellites we rely on smashed to smithereens. This nightmare scenario is known as the Kessler syndrome.

It is clear that if combatants start blowing up each other’s satellites, it risks others not involved in the conflict.

“There is a rule in humanitarian law that says that when conducting a military operation you must choose the method that produces the least collateral damage,” says Schmitt. “So blowing up satellites must be operations of last resort – at least I hope so.”

But, as yet, there is no international law about the creation of space debris. “We need new legal restrictions,” says Wörner, who is putting together a proposal for an ESA programme of space safety and security to safeguard civilian access to space. The agency will develop this proposal over the next 18 months and present it for funding to European science ministers in 2019.

Schmitt is also working to clarify the law. He is part of an international consortium of law, military and space experts who are putting together TheWoomera Manual on the International Law of Military Space Operations.

It is an international project that is being sponsored by the University of Exeter, UK, UK; the University of Nebraska, USA; the Universiry of Adelaide and the University of New South Wales, Australia. There are also supporting establishments such as Xiamen University, China, and the US Naval War College, Rhode Island.

“We’re trying to get ahead of the curve. We want to start thinking through the rules of the game before we start playing the game,” says Schmitt. “We did not do that for cyber [war]. It got ahead of the lawyers and we have been playing catch up ever since.”

But are rules really that useful in war? Surely, each combatant simply wants to win.

“I’m not naive,” says Schmitt, “You need to be realistic about what the enemy are likely to do, but compliance with the law is a force multiplier. There is a natural inclination to believe that if you play by the rules and the opponent doesn’t, then the opponent has an advantage. But in fact, you have an advantage because if you comply with the law, your coalition is going to stay intact.”

He explains that in the aftermath of 9/11, when the US started to torture prisoners and hold them at so-called black sites, even close allies stopped cooperating and refused to share intelligence.

Last year, under Schmitt’s direction, The Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare was finally published. The Dutch government now conducts the Hague Process, where it sends teams around the world to teach governments this cyber law.

“I would hope we do this in the space context, so it is not just a book on the shelf,” says Schmitt.

And the clock is ticking. With international tensions on the rise, and seemingly daily escalations in the audacity of cyber-attacks, it may only take the smallest trigger to start attacking the satellites. Schmitt has a clear warning: “We cannot wait until it starts happening to then try to figure out what the law is. By then, it will be too late.”

Stuart Clark writes the Guardian’s Across the universe blog

Where do we go from here? The tools of a future conflict

Missiles

The US, Russia and China have all demonstrated their capability of launching missiles from Earth to intercept and destroy satellites. The US began a research programme to shoot down spacecraft almost as soon as the Russians launched the first satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957.

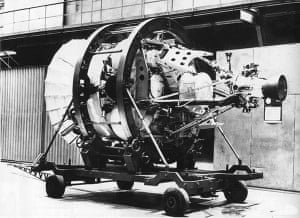

Russia also began to think about taking out enemy satellites. In the early 1960s, they tested a system called Istrebitel Sputnik (fighter satellite). It was designed to approach its target and then explode, destroying both satellites.

Although the project was eventually disbanded, testing and development of similar systems have continued on and off ever since. In 2015, the Russians successfully tested an anti-satellite missile.

In the aftermath of the 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test (see above), America launched its own missile, destroying a failed spy satellite that was gradually falling back to Earth. However, such destructions can cause dangerous clouds of space debris, which endanger other satellites indiscriminately.

Directed energy weapons

In the 1970s, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, California, worked on Project Excalibur, which aimed to detonate a nuclear weapon in space. Lasers would then focus the resulting x-rays on to as many as 50 incoming missiles at a time to destroy them as they arced through space towards the US and its allies. The project collapsed through lack of progress and funding, however.

Currently, the primary use of lasers is to dazzle spy satellites and stop them gathering their information. China and Iran are reported to have done this to US satellites and it is likely that the west does the same in return. If the laser lingers on the satellite cameras for too long, however, it could permanently blind the satellite rather than just temporarily dazzle it. The legality of actually damaging a satellite in this way is another grey area.

Hacking satellites

This is probably where the first strike in a space war will take place. There have been a number of satellite hacks reported over the years, including to Nasa climate satellites in 2007 and 2008 but no permanent damage was reported.

In a conflict, commands to fire thrusters could set the spacecraft spinning helplessly or move them into useless orbits. On Earth in 2009, a purposely written piece of malicious software commanded Iranian nuclear centrifugesto spin too fast, damaging them beyond repair. The same could happen with satellites. Even now, hackers could be working to place artificially intelligent software routines (logic bombs) inside spacecraft control systems. These could be activated when a certain signal is received or an onboard condition is met.

The European Space Agency is currently looking at safeguarding its satellites by developing quantum encryption techniques for future missions. “We have to take cyber attacks seriously,” says director general, Jan Wörner.

Attack satellites

Think of this as the brute force approach. One satellite simply goes up to another, hits it and knocks it out of orbit. This could damage the attacker as well, so a more sophisticated version is a spacecraft equipped with mechanical arms that grapple the target, pulling off solar panels or instruments.

In other words, it’s robots fighting in space. And if that sounds a bit too much like science fiction, think again says Martin Schmitt of the University of Exeter.

“I don’t think it’s science fiction at all. A lot of these programmes are highly classified, but people in the [military] business are talking about those kinds of operations,” he says.

On 6 March this year, Defense Intelligence Agency director Lt Gen Robert P Ashley Jr testified before the US Senate armed services committee in Washington, DC, and said that Russia and China were developing weapons for use in a space war that included such satellites. It’s a sure bet the US is developing them too.

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading The Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. Our independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

Unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want our journalism to remain free and open to everyone. Democracy depends on reliable access to information. By making our journalism publicly available, we’re able to hold governments, companies and institutions to account, and offer our diverse, global readership a platform for debate and commentary. This encourages us all to challenge our opinions on what’s happening in our world. By supporting The Guardian – and just giving what you can afford – you can help us ensure that everyone has access to critical information for years to come.

Courtesy: The Guardian